News conference, Washington, D.C., reported in The New York Times (February 25, 1971), p. 38.

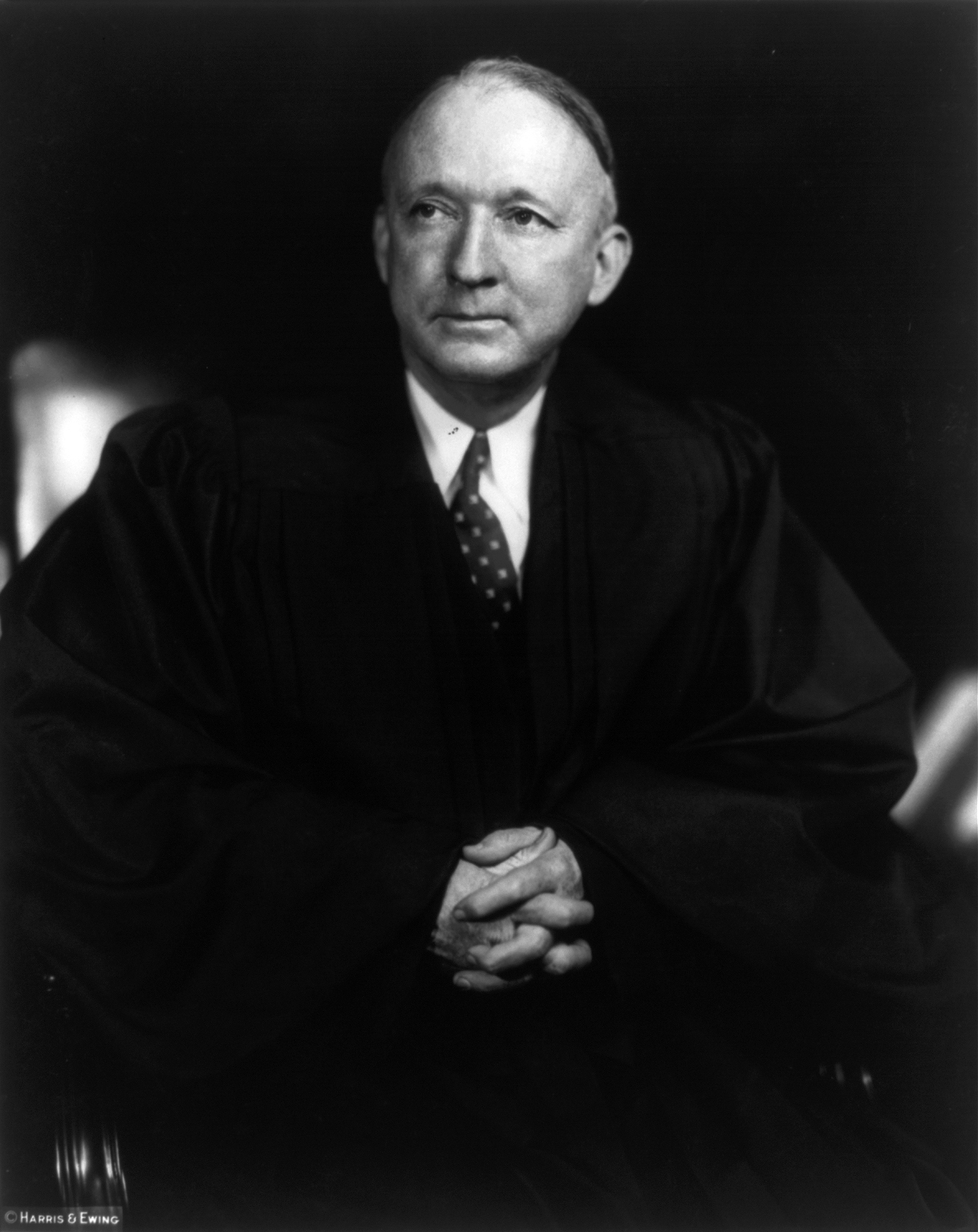

Блэк, Хьюго: Цитаты на английском языке

Concurring in New York Times Co. v. United States, 403 U.S. 713 (1971).

Dissenting in Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections, 383 U.S. 663 (1966).

Concurring in New York Times Co. v. United States, 403 U.S. 713 (1971).

Контексте: The word 'security' is a broad, vague generality whose contours should not be invoked to abrogate the fundamental law embodied in the First Amendment. The guarding of military and diplomatic secrets at the expense of informed representative government provides no real security ….

Writing for the court, Engel v. Vitale, 370 U.S. 421 (1962).

Контексте: Our Founders were no more willing to let the content of their prayers and their privilege of praying whenever they pleased be influenced by the ballot box than they were to let these vital matters of personal conscience depend upon the succession of monarchs. The First Amendment was added to the Constitution to stand as a guarantee that neither the power nor the prestige of the Federal Government would be used to control, support or influence the kinds of prayer the American people can say -- that the people's religions must not be subjected to the pressures of government for change each time a new political administration is elected to office. Under that Amendment's prohibition against governmental establishment of religion, as reinforced by the provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment, government in this country, be it state or federal, is without power to prescribe by law any particular form of prayer which is to be used as an official prayer in carrying on any program of governmentally sponsored religious activity.

“I read "no law . . . abridging" to mean no law abridging.”

Concurring opinion, Smith v. California, 361 U.S. 147 (1959).

Контексте: The First Amendment's language leaves no room for inference that abridgments of speech and press can be made just because they are slight. That Amendment provides, in simple words, that "Congress shall make no law... abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press." I read "no law... abridging" to mean no law abridging.

Writing for the court, Everson v. Board of Education, 330 U.S. 1 (1947).

Writing for the court, Smith v. Texas, 33 U.S. 129 (1940).

And they knew that similar persecutions had received the sanction of law in several of the colonies in this country soon after the establishment of official religions in those colonies. It was in large part to get completely away from this sort of systematic religious persecution that the Founders brought into being our Nation, our Constitution, and our Bill of Rights with its prohibition against any governmental establishment of religion.

Writing for the court, Engel v. Vitale, 370 U.S. 421 (1962).

Dissenting in Green v. United States, 365 U.S. 301, 309-310 (1961).

Writing for the court in Everson v. Board of Education, 330 U.S. 1 (1947) about the consequences of the First Amendments Establishment Clause and Free Exercise Clause for the separation of church and state.

Writing for the court, Korematsu v. United States, 33 U.S. 124 (1944).

Writing for the court, Chambers v. Florida, 309 U.S. 227 (1940).

Writing for the court, Everson v. Board of Education, 330 U.S. 1 (1947).

Concurring opinion, Yates v. United States, 354 U.S. 298 (1957).

Writing in 1968, as quoted in "An open letter to DNC Chair Debbie Wasserman Schultz" https://web.archive.org/web/20150630102356/http://spectator.org/articles/63244/will-democrats-apologize-slavery-and-segregation (25 June 2015), by Jeffrey Lord, The American Spectator

Writing for the court, Korematsu v. United States, 33 U.S. 124 (1944).

On due process, dissenting in In Re Winship, 397 U.S. 358 (1970).

Writing for the court, McCollum v. Board of Education, 333 U.S. 203 (1948).

Concurring in New York Times Co. v. United States, 403 U.S. 713 (1971).

Writing for the court, Korematsu v. United States, 33 U.S. 124 (1944).

Illinois v. Allen, 397 U.S. 337, 343 (1970).

James Madison Lecture at the New York University School of Law (February 17, 1960).

Concurring in New York Times Co. v. United States, 403 U.S. 713 (1971).

Majority opinion in Wesberry v. Sanders, 376 U.S. 1 (1964)