„В уме нет ничего, что не было бы прежде дано в чувстве.“

ум

Источник: Трактат о Первоначале .

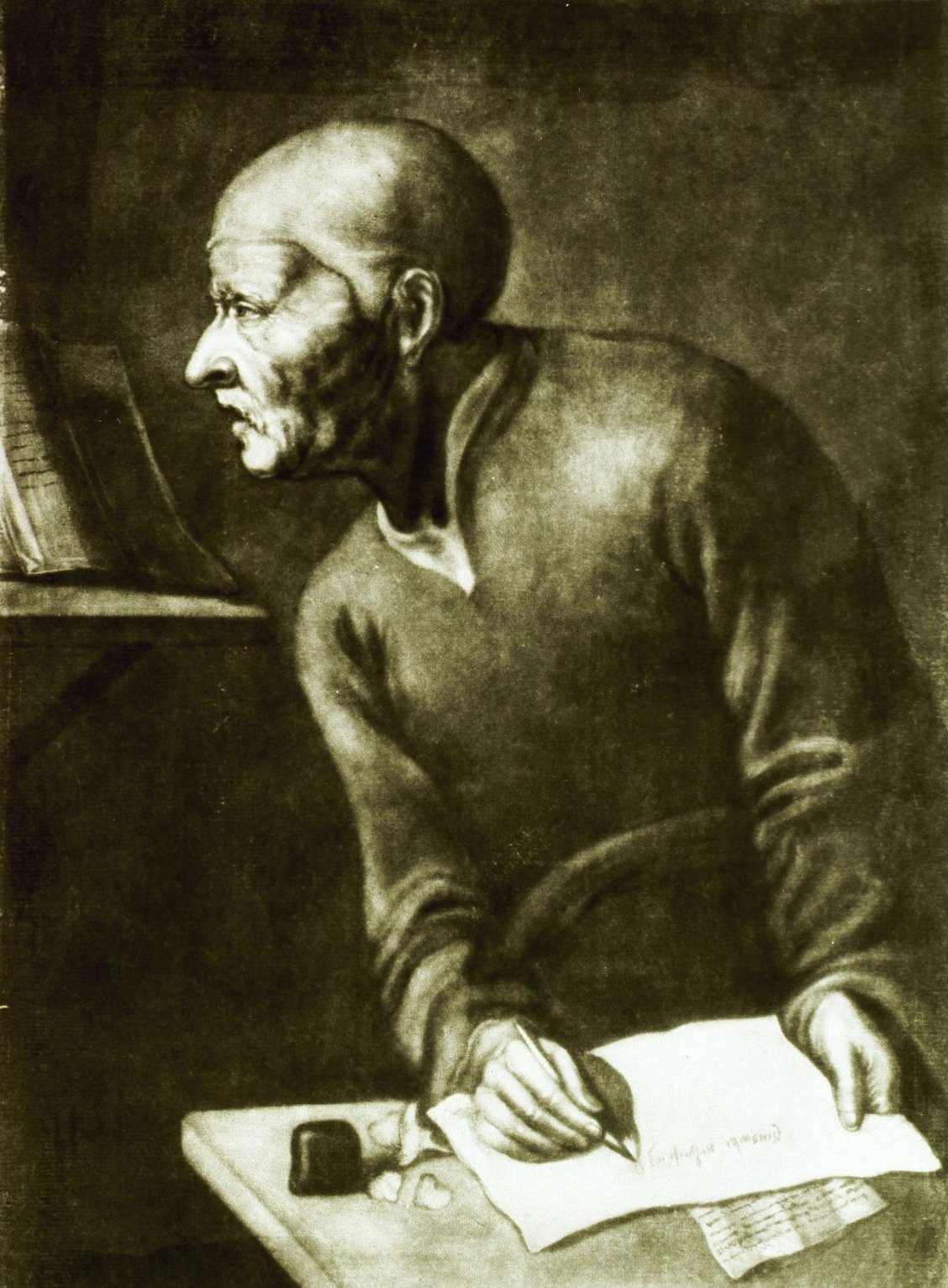

Блаженный Иоа́нн Дунс Скот — шотландский теолог, философ, схоластик и францисканец.

Наряду с Фомой Аквинским и У. Оккамом, Дунс Скот, как правило, считается наиболее важным философом-теологом Высокого Средневековья. Он оказал значительное влияние на церковную и светскую мысли. Среди доктрин, сделавших Скота известным, — такие, как: «Univocity of being», где существование — наиболее абстрактное понятие, применимое ко всему существующему; формальное различие — способ отличия различных аспектов одного и того же; идея конкретности — свойства, присущего каждой отдельной личности и наделяющего её индивидуальностью. Скот также разработал комплекс аргументов в пользу существования Бога и доводы в пользу Непорочного зачатия Девы Марии.

По мнению В. С. Соловьёва, он последний и самый оригинальный представитель золотого века средневековой схоластики и в некоторых отношениях предвестник иного мировоззрения. Получил прозвище Doctor subtilis за проникающий, тонкий образ мысли.

Дунс Скот внес вклад в классическую логику, сформулировав закон, названный потом в его честь.

Wikipedia

„В уме нет ничего, что не было бы прежде дано в чувстве.“

ум

Источник: Трактат о Первоначале .

„Верую, Господи, тому, что говорит Твой великий пророк, но, если можно, сделай так, чтоб я знал.“

Источник: Фраза, которую цитирует Лев Шестов в книге «Афины и Иерусалим» (Шестов Л. Сочинения: В 2 тт. — М.: Наука, 1993. — Т. 1. — С. 330.). Как поясняет комментатор Шестова Анатолий Ахутин (Шестов Л. Сочинения: В 2 тт. — М.: Наука, 1993. — Т. 2. — С. 467.), имеется в виду самое начало трактата Дунса Скота «О первоначале всех вещей» (De primo rerum omnium principio), но Шестов цитирует его в вольном пересказе из книги Этьена Жильсона «Дух средневековой философии» (L’Esprit de la philosophie médiévale).

“If all men by nature desire to know, then they desire most of all the greatest knowledge of science. So the Philosopher argues in chap. 2 of his first book of the work [Metaphisics]. And he immediately indicates what the greatest science is, namely the science which is about those things that are most knowable. But there are two senses in which things are said to be maximally knowable: either [1] because they are the first of all things known and without them nothing else can be known; or [2] because they are what are known most certainly. In either way, however, this science is about the most knowable. Therefore, this most of all is a science and, consequently, most desirable…”

sic: si omnes homines natura scire desiderant, ergo maxime scientiam maxime desiderabunt. Ita arguit Philosophus I huius cap. 2. Et ibidem subdit: "quae sit maxime scientia, illa scilicet quae est circa maxime scibilia". Maxime autem dicuntur scibilia dupliciter: uel quia primo omnium sciuntur sine quibus non possunt alia sciri; uel quia sunt certissima cognoscibilia. Utroque autem modo considerat ista scientia maxime scibilia. Haec igitur est maxime scientia, et per consequens maxime desiderabilis.

sic: si omnes homines natura scire desiderant, ergo maxime scientiam maxime desiderabunt. Ita arguit Philosophus I huius cap. 2. Et ibidem subdit: "quae sit maxime scientia, illa scilicet quae est circa maxime scibilia".

Maxime autem dicuntur scibilia dupliciter: uel quia primo omnium sciuntur sine quibus non possunt alia sciri; uel quia sunt certissima cognoscibilia. Utroque autem modo considerat ista scientia maxime scibilia. Haec igitur est maxime scientia, et per consequens maxime desiderabilis.

Quaestiones subtilissimae de metaphysicam Aristotelis, as translated in: William A. Frank, Allan Bernard Wolter (1995) Duns Scotus, metaphysician. p. 18-19

“We speak of the matter [of this science] in the sense of its being what the science is about. This is called by some the subject of the science, but more properly it should be called its object, just as we say of a virtue that what it is about is its object, not its subject. As for the object of the science in this sense, we have indicated above that this science is about the transcendentals. And it was shown to be about the highest causes. But there are various opinions about which of these ought to be considered its proper object or subject. Therefor, we inquire about the first. Is the proper subject of metaphysics being as being, as Avicenna claims, or God and the Intelligences, as the Commentator, Averroes, assumes.”

loquimur de materia "circa quam" est scientia, quae dicitur a quibusdam subiectum scientiae, uel magis proprie obiectum, sicut et illud circa quod est uirtus dicitur obiectum uirtutis proprie, non subiectum. De isto autem obiecto huius scientiae ostensum est prius quod haec scientia est circa transcendentia; ostensum est autem quod est circa altissimas causas. Quod autem istorum debeat poni proprium eius obiectum, uariae sunt opiniones. Ideo de hoc quaeritur primo utrum proprium subiectum metaphysicae sit ens in quantum ens (sicut posuit Auicenna) uel Deus et Intelligentiae (sicut posuit Commentator Auerroes.)

Quaestiones subtilissimae de metaphysicam Aristotelis, as translated in: William A. Frank, Allan Bernard Wolter (1995) Duns Scotus, metaphysician. p. 20-21

Scotus (c. 1300), Ordinatio 3.37 as cited in: Peter A. (2004) "Kwasniewski William of Ockham and the Metaphysical Roots of Natural Law" in: The Aquinas Review, 2004